This text was originally published in The Spectator.

A wave of totalising race-first exhibitions has swept through UK art institutions of late. The National Portrait Gallery’s remit of ‘reflecting’ British society could reasonably make one wary of its turn at the same project. Indeed, a false, stilted language accompanies curator Ekow Eshun’s The Time is Always Now. To have some twenty artists “reframing the black figure” somehow sounds both ambiguous and politically predetermined.

Eshun has long been invested in the artistic black diaspora. His 2022 Hayward Gallery show In the Black Fantastic played on fantasy and Afrofuturism and had artists make new worlds that would take over the failing present. This time, however, he resorts to a safe and comfortable cadre of artists, many of whom, like the painter and museum activist Lubaina Himid, have featured in just about every other institution’s race and decoloniality-themed blockbuster. Works by the likes of dub club abstractionist Denzil Forrester and barbershop reminiscer Hurvin Anderson who rose to prominence between earlier waves of interest in black creativity mix with images by celebrated American chroniclers of urban life Henry Taylor and Jordan Casteel.

These are steady hands, and Eshun does little to challenge their aesthetic conservatism. In exchange, they pretend not to notice that he doesn’t challenge the institution’s race platitudes, either. In parts of the show, skin colour is a painter’s superpower. In others, the root of historical trauma. The gallery thinks nothing of bridging continents yet turns a blind eye to social class. It’s not clear if it’s the artists or the viewers who are to believe these contradictions.

One way to evaluate this proposition is to consider the material claims made by the museum on behalf of the work. Under such scrutiny, what unites these paintings by Brits, Kenyans, and Americans is more often a trendy hashtag than the “lived reality” to which Eshun appeals. To look for a common denominator in the concerns of Amy Sherald best known for her off-colour official portrait of Michelle Obama and the Turner Prize nominee Barbara Walker’s sometimes naively expressed concern with art-historical absence is to fall for this exaggeration.

[ppwp passwords=”black bruno” whitelisted_roles=”administrator, editor” headline=”” description=”This text was published in The Spectator behind a paywall.” desc_below_form=”Get in touch if you’d like to read this text.” desc_above_btn=”” label=”To continue reading, you need to enter the password.” error_msg=”Please try again or get in touch if you don’t know the password.” ]Applying this critique to one show after another, however, is futile and only meets with the institution’s outright refutation. In this exhibition’s introduction, for example, the gallery thanks Eshun for his emotional labour, implying that to question his method would be a breach of etiquette.

The alternative is to ignore the narrative and read the works entirely on aesthetic terms. An oversized and dazzlingly golden bronze statue of a young woman in casual sports attire and braided hair looms over the gallery’s entrance. Thomas J Price uses 3D scans to create his ‘everyman’ figures, so that they could, in principle, be young, black, and from Croydon. But because this nod at the universality of the black experience is styled by Sports Direct and Price’s subjects are composites of multiple sitters, this work turns to commodity fetish. When in a section of the exhibition dedicated to “aliveness” the Brooklyn-based Tovin Ojih Odutola tries to show “a multiplicity of identities” of her Nigerian ancestry, she likewise fictionalises them and poses them in interiors reminiscent of the Soho House franchise.

On the canvas, concern with appearances and status becomes this diaspora’s trademark. Claudette Johnson’s self-portrait as a middle-aged woman reckoning with Picasso’s notorious African masks projects understandable consternation rather than daring. Nideka Akunyili Crosby’s aspirational anecdotes of hyphenated lifestyles in Los Angeles barely compensate for their inherent mundanity with overly opulent decoration.

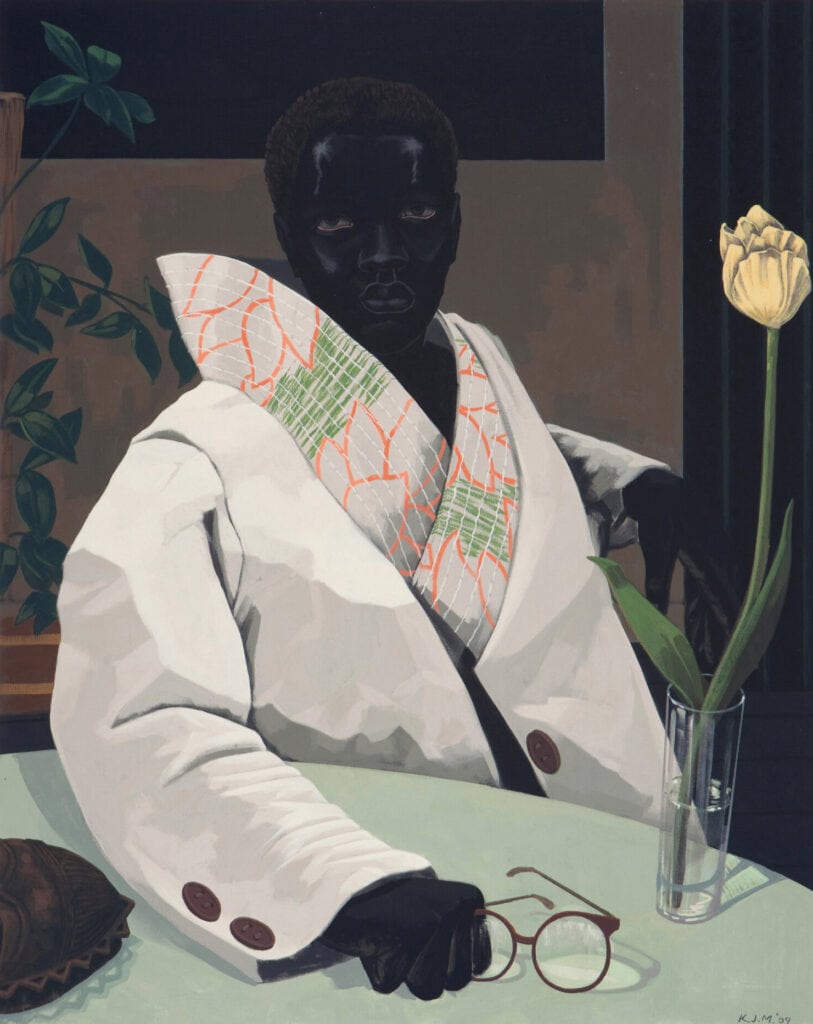

As any winner of the Gallery’s annual portrait competition would attest, the trick to making it in the art world is to choose one’s sitters wisely. Of the three works by the acclaimed American painter of the black figure Kerry James Marshall included in the exhibition, the most striking is the Portrait of a Curator, a slick image of a glamorous, expensively dressed woman. Neither artists, nor the museum ever tire of navel-gazing.

At this point, one may wonder why race, rather than art world standing should be the exhibition’s focus. The proposition is a far cry from the infamous 1993 Whitney Biennial which featured Daniel J. Martinez’s slogan “I can’t imagine ever wanting to be white” and ushered identity politics into contemporary art. Establishing race as an aesthetic category then held political potential which many of the artists featured here explored in their work. But that power is sorely lacking when the institution itself ventriloquises radicalism in works that by now have different, often equally pressing concerns. To predicate their success on subscribing to the DEI department’s tenets does everyone a disfavour.

Next to the Sunday supplement portraits that market Eshun’s exhibition, those works that directly speak to traumatic legacies are harder to parse. They do, however, deservingly capture attention. The American Noah Davis’ account of the 1921 Tulsa race massacre, for example, is both unnerving and trippy. Dying bodies line the painting’s background but it is a pair of pheasants caged under lumps of gold that dominates the picture. The canvas thus blends the historical record, already heavily paraphrased by the then 26-year-old painter some 87 years after the event, with pure fantasy. Despite itself, it reveals the artist’s desire to escape.

Turning to lowercase conservative aesthetics is a rite of passage for an artist keen to secure a place in art history. This isn’t a character flaw and Eshun’s exhibition rightly celebrates the painterly accomplishment of a generation of artists whose former social and political practices are today a vital part of the canon. There is a tension, however, between the bourgeois consciousness evident in the paint and the institution’s goading call to see all images through a race prism. Intersectionality, it turns out, finds limits in the museum.

[/ppwp]The Time is Always Now continues at the National Portrait Gallery until 19 May.

Main image: Noah Davis, Black Wall Street, 2008, Oil and acrylic on canvas, The Studio Museum in Harlem. Photo: Adam Reich.