The arts might have hoped for a clean slate – but the post-pandemic art world is unlikely to be much better than the old one.

For many, particularly the urban middle classes, the denial of access to the culture they knew was the first shock of the pandemic. In the early days of the UK’s coronavirus lockdown, the plight of the arts featured in media commentaries almost as heavily as the far more dramatic events in hospitals. This was perhaps because the government-mandated closures of theatres, galleries and museums heralded what was still to come for restaurants, bars, shops and community centres.

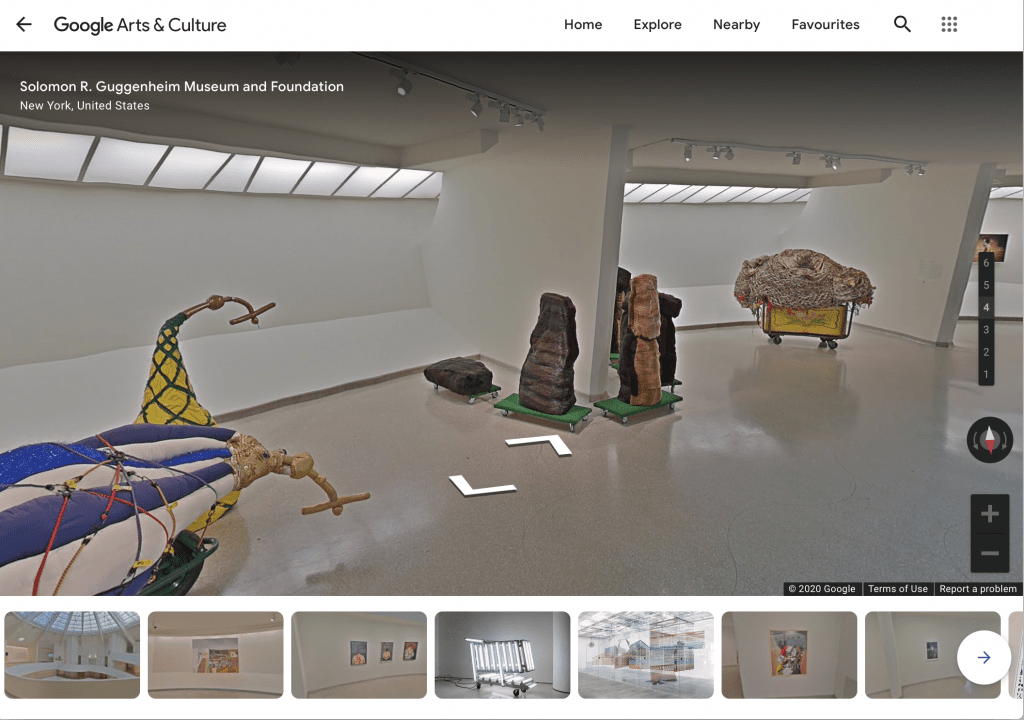

And so the art world was raptured away into the new universal museum for anxious souls: the Internet. Alas, after an early explosion of online exhibitions, many an Instagram Live performance started off to an audience of two dozen before losing half to technical difficulties. Screen fatigue and existential anxieties meant that the initial explosion of interest in online production and consumption of art has waned almost as quickly as it arose.

While competing with Netflix for bandwidth and attention spans, the arts began to count their losses. Emergency government grants and philanthropic support have helped to stabilise the short-term incomes of organisations and artists, but many should not expect to recover with ease, if at all. As days passed under lockdown, the art world was shaken by reports of New York’s MoMA unceremoniously sacking its education staff while their endowment stands at $1 billion, or London’s Southbank Centre having to remain closed until next spring due to a shortage of funds.

The view from the precipice can be as exhilarating as it is terrifying. In the trauma of cancelled exhibitions, scrapped projects, postponed residencies – not to mention lost incomes – one can hear a cry for change, and a desire to emerge into a different reality.

The show business glamour of the art world: the globetrotting and champagne-fuelled networking in Venice or ArtBasel that only few can truly afford has been wearisome for some time. Calls for reform have been a constant refrain in the rhythm of biennials, conferences, art fairs and exhibition openings. In the publicly-funded institutional sphere, contemporary art also trod an unsustainable path, taking on a heavy burden of driving social change, promoting and enacting the most ambitious of political agendas on the tightest of budgets.

All change

The opportunity seems too good to miss. With every constituent of the contemporary art world, from the international auction house to the freelance gallery technician, disturbed to the core, the pandemic offers a moment to reflect and plan a recovery that’s more sustainable and equitable.

Similarly-poised campaigns in other areas have seized the moment of the pandemic – we all marvelled at the photographs of crystal clear waters in Venice and applauded plans for car-free city centres in Paris and London – so why couldn’t art?

A desire for change was voiced in the statements of museum directors, countless editorials, and plenty of Zoom seminars with artists. A selection of art press headlines in early April proclaimed “the end of the art world as we know it,” that “the art world has the opportunity to be truly open” and that “life after the coronavirus will be very different.” A curator even observed that “before the lockdown, the public was agitating for a revolution in […] museums.”

But were they? What could one expect from an industry riven by internal contradictions and a sustainability score of an oil tanker? However glossy, democratic, progressive and inviting the Western art world appeared to its lay audiences, it had long suffered from all the ailments of late capitalist commodity culture, including widespread exploitation of labour, vast inequalities in income and wealth, inexcusable environmental record, and friction at the boundary of public good and private luxury.

Despite decades of negotiation and public self-flagellation – symbolised by institutional critique, a movement which honed in on the inescapable corruption of the art world and the impossibility, in the words of Andrea Fraser, of participating without becoming synonyms with its complexities – there is no consensus on what a better art world and art could be.

No premonitions

For associate editor of the Spectator Mary Wakefield, “getting coronavirus does not bring clarity.” On suffering trauma, Wakefield naturally hoped for a premonition. She describes the fatigue, fever and whooping anxiety of the illness, all of which go unrewarded. The world’s artists, museums, and art fairs alike have suffered unprovoked damage too, and they are looking for some sort of awakening in compensation.

History does offer some grand precedents which almost justify this hope. In the wake of the Second World War, the arts came back stronger, notes Charlotte Higgins. Picasso’s Guernica, painted in response to the atrocities of the Spanish Civil War, is one of art’s most powerful expressions of anger and pain and has symbolised the anti-war movement since. And sure, time may bring significant art. Maya Binkin points to Henry Moore, Egon Schiele and Ai WeiWei as examples of artists whose practices responded to trauma to their strengths.

The sheer amount of artistic energy recently poured into Zoom alone should see a new art take form, and meeting a digital-only audience will encourage new ideas. This will take time, though. Jörg Heiser describes much of the ‘quarantine art’, including projects commissioned by the world’s foremost institutions, as ‘empty heroics’. The artist Simon Fujiwara’s now deleted Instagram post which cited the Diary of Anne Frank as inspiration for starting his own quarantine diary comes to mind.

But where for some artists, the experience of lockdown, illness or losing loved ones may result in a profound change of practice, there is no guarantee that the structural issues of their industry will be touched by it at all. As Michel Houellebecq, the bad boy of contemporary French literature proclaimed, the world is likely to be the same, only a little worse after the ‘banal’ virus. The changes we may see are the same ones we could have predicted years ago: an encroaching obsolescence of human relationships that drives the world into the hands of ever-consolidating business and technological interests.

Saving the arts

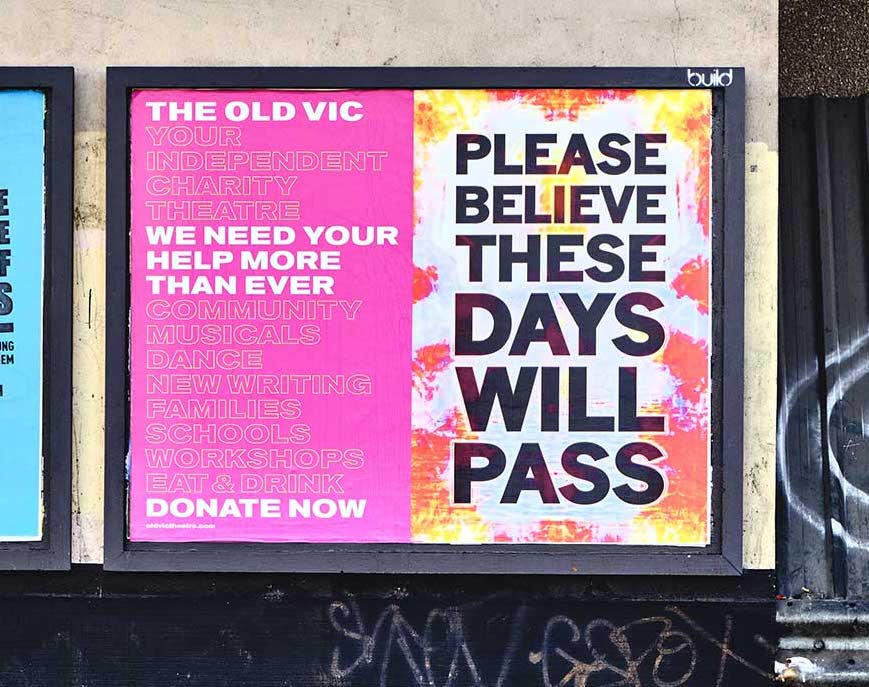

Reading the statements of arts institutions which accompanied the lockdown closures, one could be touched by their almost magnanimous care for their audiences and staff. In preparing their quarantine programmes, outfits like Tate Modern had a head start, but even smaller institutions soon found ways to open up their archives, stream endless video, and host live conversations.

For a moment, it seemed that this move to the virtual could have a democratising effect. Audiences who had previously been excluded from accessing cultural experiences – through economic, geographic or educational obstacles – could now all point and click their way towards artistic enlightenment. Blockbuster exhibitions turned free and even art fairs like Frieze that normally cater to a narrow base of collectors and professionals went online, with price lists visible to all.

That this opening effect will last is far from a given. If will was all that was needed to make existing art materials available free of charge, why hadn’t this happened a long time ago? Free exhibitions that so generously opened online in March were by May were giving way to fundraising appeals, print sales and charity auctions.

One may also read the cries of solidarity between the art world and its audiences as a thinly veiled attempt to ensure self-preservation in the inevitable economic downturn that will follow the pandemic. By highlighting the public relevance of the arts in a time of crisis, the arts are preparing their argument for public support in the future.

While for many advocates the value of the arts is universally understood, some tug at the purse strings of an entirely different department altogether. In an attempt to secure patronage for his institution, the vice-chancellor of the Royal College of Art in London Paul Thompson made a perplexing argument that “art schools play an essential role in supporting the medical industry”.

Faced with a shock, the first instinct of the art world colossus has been to seek stability in the very same structures of capitalism that made banks ‘too big to fail’ in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. Those actors who were strongest before the pandemic also stand the highest chance of accessing the support – that is funding – that will allow them to weather the storm.

The giants of the commercial art world, including the blue chip galleries that disproportionately benefit from the art market’s stellar rise of the past decades, have displayed nothing but optimism for the future. Marc Glimcher, director of Pace gallery, spoke of his personal experience of Covid-19 with an air of martyrdom, chastised himself for waste of relentless international travel his job entails, but stopped short of resolving to make any changes. Former gallerist and art fair founder Elisabeth Dee, hopes for more cooperation between galleries in the future – but also for interest-free credit and subsidies for art fairs.

No (good) new ideas

In the history of revolutions, those movements which were successful in bringing about lasting change were underpinned by strongly-developed ideologies which permeated their society. In the French Revolution, the complete permeation of Enlightenment ideals in the aristocracy and bourgeois classes created a parallel ideology to absolutism that was ready to replace it. And, frustrated by the endless postponements of the true revolution, the Bolsheviks simply created their own shadow government structure. In the smoldering ruins of 1917, they were the only ones left with an idea, any idea, and thus took power.

For things to change for good, Covid-19 would need to have more in common with a revolutionary movement than with an evolutionary process. There may have been many revolutionary ideas in the art world, but none of them have taken centre stage.

If things change, they will do so because of market failure, not because the industry willed it. The art world is just one instrument of many in the financialised arsenal of control. In the beginning of the pandemic, Naomi Klein’s doctrine of ‘disaster capitalism’ was typical of the liberal intellectual response: the ‘unprecedented’ nature of the event was in fact well-rehearsed and a familiar tool of late capitalism for extending control over its subjects.

In the art world torn apart by its own inequities while it preaches revolution to its audiences, a practical, scalable methodology for change is lacking. As long as artists and their institutions seek artistic freedoms, social relevance, fame and profits at the same time, they will remain stuck in the vicious circle Klein describes.

Disaster capitalism has its victors, but it also requires martyrs, and artists are only happy to oblige. When a study suggested that artists were amongst the professions least likely to contract Covid-19, second only to lumberjacks, ArtMonthly sighed with indignation that the scientists clearly hadn’t heard of social practice, while The New York Times shed a tear for a generation of artists graduating this year who will miss out on being ‘discovered’, despite having paid their tuition fees.

Sacrifice is arguably self-seeking, if not economically, then symbolically. Now that most arts institutions have moved their discursive practices online, making them free to all, one can tune in on artists, curators and thinkers across the globe discussing their difficulties and anxieties in uniformly grim tones infused with perfunctory hopes for a brighter aftermath.

Alexander Garcia Düttmann laments the compliant response of art schools, historically the breeding grounds of social critique, to the conditions of the pandemic: artists and the academy “are content with reproducing bland social therapy discourses”. This is hardly new: plenty of the social practice projects that are the stalwart of museum and gallery engagement and education programmes confuse the performance of preordained ameliorative services with meaningful critique or emancipation.

Jörg Heiser suggests that artists pay lip-service to social causes while cultivating the image of a heroic dissenter precisely because “not doing so would require them to admit […] an unsettling sense of existential insecurity.” This would damage the myth of the artists as an truth-seer immune from petty concerns, “so the typical panic reaction has been to rehash preconceived notions to fit new circumstances.”

One bold suggestion has been mega-curator Hans Ulrich Obrist’s ambitious proposal to meet the challenges of the post-pandemic art world with a programme akin to the 1930s US Public Works Arts Projects. The post-depression programme commissioned thousands of works of art and gave employment to hundreds of artists, and has gone down in history as the greatest state-supported art initiative, outside perhaps of communist China and Bolshevik Russia.

In the coming years, many artists will surely relish an opportunity of employment decorating state schools and hospitals – many do so already – but Obrist’s proposal fails to take into account capitalism’s ability to wield the soft power of art to its own advantage, and artists’ wary reaction to its advances. Many of the well-meaning public art projects of the past thirty years have served only to paper over the cracks in the social fabric of the state, making their authors complicit with the very same ideologies they oppose. The public art works for the 2020s will likely be more private than public too, and as Tom Morton observes strolling through art-fuelled place-making projects, this renders them susceptible to all the nepotistic corruption of their sponsors.

No absolution in sight

Who will be the winners of the post-pandemic art world? The short answer is simple: the same actors who were ahead at the outset. The shaken market for art commodities, for art audiences and for art education will find ways to consolidate. Where it innovates, it will seek to reduce its dependence on human factors, as is the case after every economic crash. The migration online has already provided a model that will at once allow big brands to maintain their market leads and to cut costs, and one should expect that this tendency will soon enough evolve into a profitable proposition.

If the art world fails in making its pleas to the public, philanthropists and collector-speculators, we may see a reduced demand for art, and therefore for artists, in the medium term. Were the arts subject to the same supply and demand rules as the rest of the labour market, art schools would see fewer applicants, museums and galleries would eventually pay their talent better, and the commercial art world would lose some of its allure.

But in the ensuing recession, the life of an artist may only grow in allure. Earlier this year, the UK’s Institute for Fiscal Studies reported that those studying at art and design schools achieve lower lifetime earnings than their peers who don’t go to university at all. Yet art school admissions have been rising every year: a calling for art disregards the wallet, often at its peril. And for those whose wallets are impervious to crisis, an arts education becomes an increasingly attractive dumping ground for ne’er-do-well failsons (and daughters) of the 1%, similar to the function of monasteries and nunneries in ages past for absorbing excess and unproductive elites.

The art world’s perennial internal crisis will not come to an end as a result of the pandemic. Greta Thunberg, finding that her pet cause has been overshadowed by at least two other headline-grabbing crises, exhorts us to “Fight every crisis”. But just as ‘Wars on X’ have had diminishing returns, we lack the attention span to sustain attention demanded by the layering of crises.

For the art world and its pandemics, it may learn some lessons from them, but it may not find it in its heart to share them. We need only to look to Mary Wakefield for confirmation: she shared her Covid-19 illness with her husband Dominic Cummings, Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s principal political advisor. Given that their quarantine-breaking cross-country trip met with public furore and an ill-afforded political crisis, it may have served Wakefield better to wave the experience off with a simple “I’m fine, thanks.”

Cover image: There will be no Miracles Here, Nathan Coley, 2007. Photograph Ghost of Kuji/Flickr.