This review originally appeared in The Critic.

When Andy Warhol suggested that “in the future, everyone would be famous for fifteen minutes”, he could not have predicted that this prognosis might apply to the past and that, therefore, all lives must be lived as though those fifteen minutes were now.

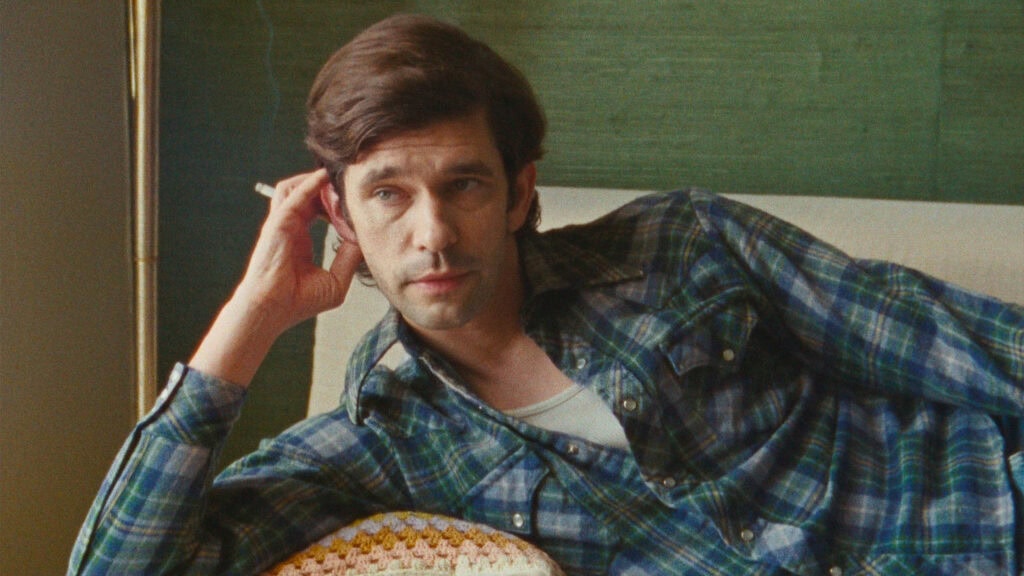

Peter Hujar’s Day, a largely soliloquistic film starring Ben Wishaw as the titular photographer, is an account of a single day in the working life of the New York artist. Hujar started out as a commercial photography assistant in the 1960s and came to prominence after Warhol included him in The Thirteen Most Beautiful Boys compilation of his Screen Tests. In 1974, when his friend Linda Rosenkrantz, played by Rebecca Hall, began her project of committing artists’ narrations of their lives to tape, Hujar was living in the East Village and supporting himself through freelance commissions from magazines. He had already made some of the images, like the portraits of his lover, the painter Paul Thek, that would define his artistic legacy.

Ira Sachs’s film, shot on grainy 16mm stock, is a near-verbatim reconstruction of Hujar’s telling of the day prior. From the outset, artist’s monologue contains as much solacious gossip and quotidian detail as it does art-historically salient highlights. He opens, for example, by name-dropping the theorist Susan Sontag, as he recalls being woken up by a phone call from an Elle magazine editor who demanded access to his portraits of the actress Lauren Hatton.

Hujar didn’t quite trust the caller’s motive, but neither is his characterisation of the conversation and its outcome entirely reliable. He voiced his anxieties about being compensated for his images, for example, and marked the gradient in professional and social standing between himself, the film star, and the editor that would have gone unacknowledged in the course of the call itself. When Rosenkrantz pauses to verify a detail, the artist admits to inadvertently telling a minor lie.

If this establishing scene seems trivial, it highlights the daily challenge of editing mundane events into narratives that, cumulatively, amount to life itself. Hujar, who was part of a vibrant artistic milieu in his lifetime and rose to cult art world status after his death from an AIDS-related illness in 1983, is at once an exceptional subject and very much the everyman in his own story.

The film’s narration is based on a recently rediscovered transcript of the lost audio recording. Sachs’s camera lingers on the portable reel-to-reel tape recorder, the telephone is a character in and of itself, and Hujar speaks of developing films in the darkroom in his bedsit studio. Technology is thus the scaffolding to this story set in the age of the printed picture magazine.

It’s hard not to compare that era’s narrative strategies with today’s throwaway Instagram story that, counterintuitively, still helps us to select and distort our memories in real time. Hujar says that he had forgotten about his meeting with Rosenkrantz and thus did not make a written account of his day. Should we believe him? His committing the events to memory is, after all, contingent entirely on his friend’s conceit of compiling a book of interviews and the presence of her microphone.

Hujar’s afternoon had consisted of a portrait session with Allen Ginsberg for the New York Times. The poet comes across as a bit of a poser, protesting that he doesn’t want a portrait, in that old-fashioned sense where the photographer and not the subject is in control. How Hujar’s process gave rise to a different kind of image is not clear from the telling.

The narration gives the impression that the writer, perhaps unintentionally, projected himself in appearances and utterances designed to be optimally reproducible by Hujar’s camera and in his words. The making of Hujar’s photograph was thus pre-emptively determined by the eyes of the newspaper’s readers the following day, or by his telling of the scene to Rosenkrantz—more so than by the moment itself.

The social vignettes recounted by Hujar suggest that the protagonists of New York’s Downtown scene, which Hujar frequented, discharged fragments of themselves for the record. It is as everyone was aware that their memories would be turned in media different to those in which they originated.

Yet the same is true of Hujar’s narration a day later and Wishaw’s reenactment of it five decades on. The film captures the artist—and, by extension, anyone who has ever told a story—in a cycle by which the mediatic telling of an event replaces the happening itself in memory. But it also clear it to zero. “I had the feeling that I had done nothing today except gotten up, photographed Allen Ginsberg and developed the film”, Hujar says, repeating for Rosenkrantz’s tape words he had already earlier uttered in recollection of the day at its end. “I often have the feeling that in my day nothing much happens, that I’ve wasted it”, he concludes, as if cocking the camera’s shutter in anticipation of the next morning.

If today’s social media is the equivalent of Rosenkrantz with her microphone—presenting an invitation, if not an obligation to create narratives—the idea that these recent technologies uniquely incentivise the production of inauthentic accounts rings hollow. Hujar’s reflection on his day is part of his extended fifteen minutes of fame; recognising this frees him from having to live it as such. TikTok and Instagram are full of records of inconsequential moments selected by their authors in the desire to turn them into material events. These fragments, discharged into the cloud, make space for future activity. Warhol’s Screen Tests were, in that sense, only tests.

It is Hujar’s photographs that has endured. (London’s Raven Row hosted an extensive retrospective of his works last year, for example.) Yet Sachs’s production refuses to contend with them. There is no art in Rosenkrantz’s apartment, and the film doesn’t cut in a slideshow of Hujar’s hits. Is this in recognition that the survival of those images was part of a different narrative that takes place off the screen?

This question is pertinent to today’s cultural scenes in New York and London, reminiscent of the Downtown of the 1960s and ’70s. Cultural events, such as the popular “reading series”, in which writers recite their works for primarily Generation Z audiences, occasion torrents of ephemeral selfies and video recordings of the crowd.

While this social media record receives lavish aesthetic attention, attendees often appear indifferent to the literary artefacts themselves. It is as though both the readers and listeners were invested more in the making of a memory of the event than in the substance that occasioned it. Today, the images of Ginsberg reading Howl to crowds are his work’s myth. Rosenkrantz, by contrast, abandoned her interview project after speaking with Hujar.