Change is in the air. It’s not clear if we are ready for it, and it may be a done deal already. Either way, the arts may be looking at an opportunity of a lifetime.

In a recent text for Hyperallergic and the Ford Foundation, the artist and writer Coco Fusco rejects the demand for artists to offer “uplifting” thoughts of a better future. Prompted to consider “our shared myths of justice and equity,” Fusco points to the histories and art movements, some of them still in living memory, that paid a heavy price for obliging the institutional desire for critique and self-flagellation. Artists who respond to their day’s urgent calls – in Fusco’s example the 1993 Whitney Biennial cohort – are judged to be “too simplistic, too strident, unmarketable, not representative, and anti-art.” Fusco concludes that it’s not new or more critical art that we need, but new institutions. The burden of creating a new future cannot fall on those (artists) who are already struggling with the museum’s duplicitous tyranny.

With the art world in turmoil, time might be right for changes from the very top. Fusco agrees: “the arts professionals that have been protesting in the streets and sending out declarations on social media are calling for institutional changes, not new aesthetic movements.”

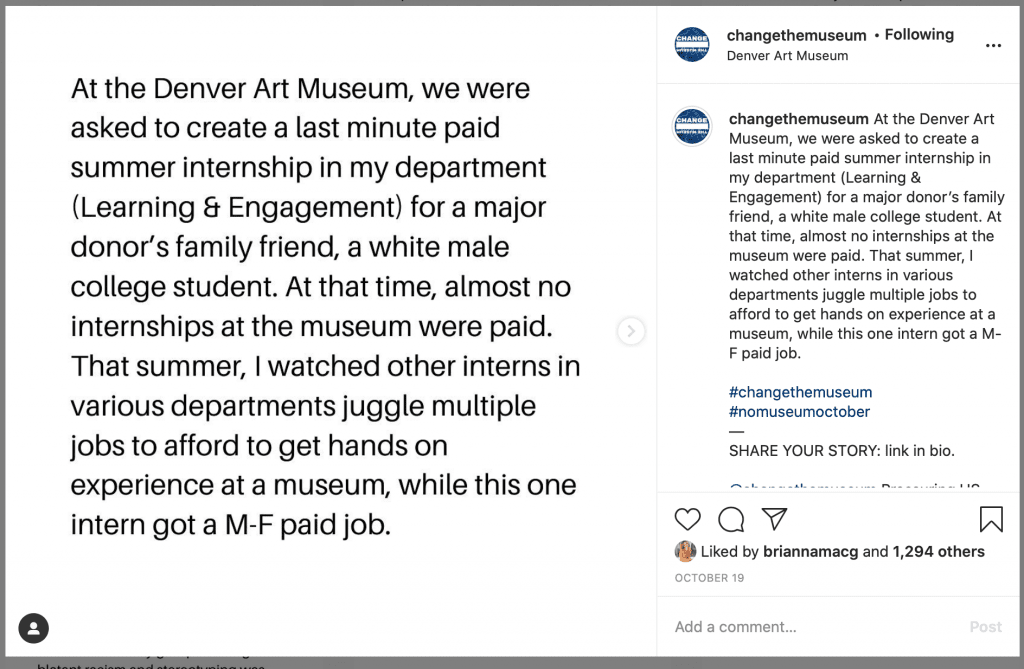

If we are to judge the state of arts institutions by the complaints of those artists and insiders who dare to raise their voices, the need for change is dire. Social media accounts like @changethemuseum and @cancelartgalleries are just some outlets that collect stories of unprofessionalism, abuse, racism and occasional law-breaking by museums and commercial galleries alike. These indictments are only the latest instalments of complaints already laid at the doors of museums and galleries by artists for years. In the eyes of many, the 21st-century art institution’s stated aspiration to rid itself of its toxic DNA has remained just that: an aspiration. All that’s new is PR.

While no-one disagrees in principle that institutions should change, just how precisely one goes about this endeavour is less clear. Who should take the initiative? Fusco doesn’t think it’s artists who should storm the barricades. Should it then be the arts professionals who are already protesting in the streets? Those arts professionals who are peers of the very same artists Fusco would like to spare from this particular struggle?

But aspects of this tug of war are already well underway, making use of both aesthetic and civic tools available to artists. Plenty of the grievances aimed at individuals and institutions – expressed anonymously, in #metoo accounts, or through mass boycotts – have been successful in denting structures of power, thereby proving that the complaints weren’t groundless. One recent example of this is the resignation of the arms manufacturer and arts philanthropist Warren Kanders from the board of the Whitney following pressure from artists.

That the words ‘arms manufacturer’ and ‘arts philanthropist’ lie so closely together comes, in the words of Jenny Holzer, as no surprise; it also exposes as foolish the assumption that a predilection for art, however financially committed, is a conduit to moral virtue. We can’t assume, Fucsco noted, “that [social justice] is a shared value.” None of this, sadly, helps to address the ‘systemic’ problems of the institution. Not because it’d be a lifetime’s campaign to rid the museum of every tainted board member and the gallery of every unscrupulous dealer, but because the ‘systemic’ is embedded in us all.

If the art world is toxic and abusive or if it is a traitor to its stated ideals, it cannot be solely because management teams have fallen prey to the corrupting influence of donors and sponsors. It’s also unlikely that a cabal of morally bankrupt players intentionally ruins the game for everyone. What is more probable is that any individual’s commitment to the presumed shared values is subject to constant evaluation in play with their position within a social and institutional hierarchy in a way that is at once challenging and complex. While social justice and equity can be the foundations of a universal morality, the individual ethics of artists, technicians, curators, educators and managers will likely differ in response to their experiences of the institution.

We only need to look back to Andrea Fraser’s take on institutional critique for a reminder that we are all inescapably implicated in the institution’s failures, whether through our desire for its endorsement, our resentment of its refusal, or even our rejection of its primacy. To be an artist or an arts professional is to bear responsibility for all the museum’s shortcomings.

Put crudely: power corrupts, as does participation in any structure. But perhaps this experience need not be wasted on simply reproducing the very same system which corrupts in the first place. The good news in this charge is that arts professionals – and yes, artists – are the very people best placed to change the institution and to build alternatives to it. So if not us, then who?

Wherever we are is museum

Another struggle affecting most of the world may come in handy as an outsized illustration of a complex system trying to reform and break away from its zero-sum predicament. Climate change has been a preoccupation of activists and civil society for almost a decade, and many governments have now conceded that action is necessary.

Despite the almost unanimous good intentions, not much has changed, and it would be easy to apportion blame to any component of the system: the politics are too complicated, lobby interests get in the way, and there’s a looming conceptual gap between the actions of individuals and those of societies at large. On closer inspection, it turns out that it’s the difficulty of negotiating values, and not moral disagreement, that is a barrier to action: a survey of UK parliamentarians, for example, suggested that social norms and relationships between lawmakers, and not the lack of political accord, are the root of the problem.

Arguably, where the fight to reduce carbon emissions has found a relatively easy win is in innovation such as wind power, where the already existing infrastructures of manufacturing, financing and distribution have been able to come together to create a revolution while only seeking reform. In the US, the business-minded aspects of the Green New Deal have the potential to achieve similar results by simply diverting the productive focus of the ‘business as usual’ model to greener ends.

While it would be irresponsible to completely discount the role of pressures from activist groups in creating a political environment open to innovation, one must note that organisations such as Extinction Rebellion are often at odds with the very idea of business and capital. Despite this, occasionally, business and capital get things right. The key point here is that demand and innovation need to come together to create the conditions of change. The ‘system’ is unlikely to change under negative pressure alone unless it’s offered a viable and sustainable alternative.

In the art world, then, activism, protest and desire for change need to be accompanied by innovation, speculation and experimentation: the very things that artists and arts professionals are trained for. Easier said than done, of course, because unlike the energy industry, the experimental structures in the arts lack capital, and unlike engineering, the arts aren’t all that good at communicating and expanding their learning. The former may be a structural deterrent, but the latter, the industry must take some responsibility for.Both the problems are visible in the struggles of small and medium-sized arts institutions in the era of Europe’s turn away from state funding and towards private philanthropy. A 2015 study revealed that most UK organisations’ business models were stuck with the same poor ideas: desperately opening cafés and courting the same group of donors while resenting the very idea of entrepreneurialism. That among the thousands of arts professionals involved in shaping these structures, no-one had ideas that better represent the values and desires of these often young and dynamic institutions beggars belief.

The resistance of the arts towards knowledge and skills from disciplines such as management and finance comes to the detriment of both the art and its institutions. It is all too easy to dismiss management as dehumanising, corrupt and responsible for the shortcomings of institutions as we know them, while to concentrate on concentrating on community building instead is immediately rewarding. In the long run, however, wouldn’t it be better to learn – and to steal – from management such techniques that can make the communities and the institutions that artists care about stronger? Who, if not artists, will innovate and bring these new institutions to life?