This is an extended version of an essay that originally appeared in Compact.

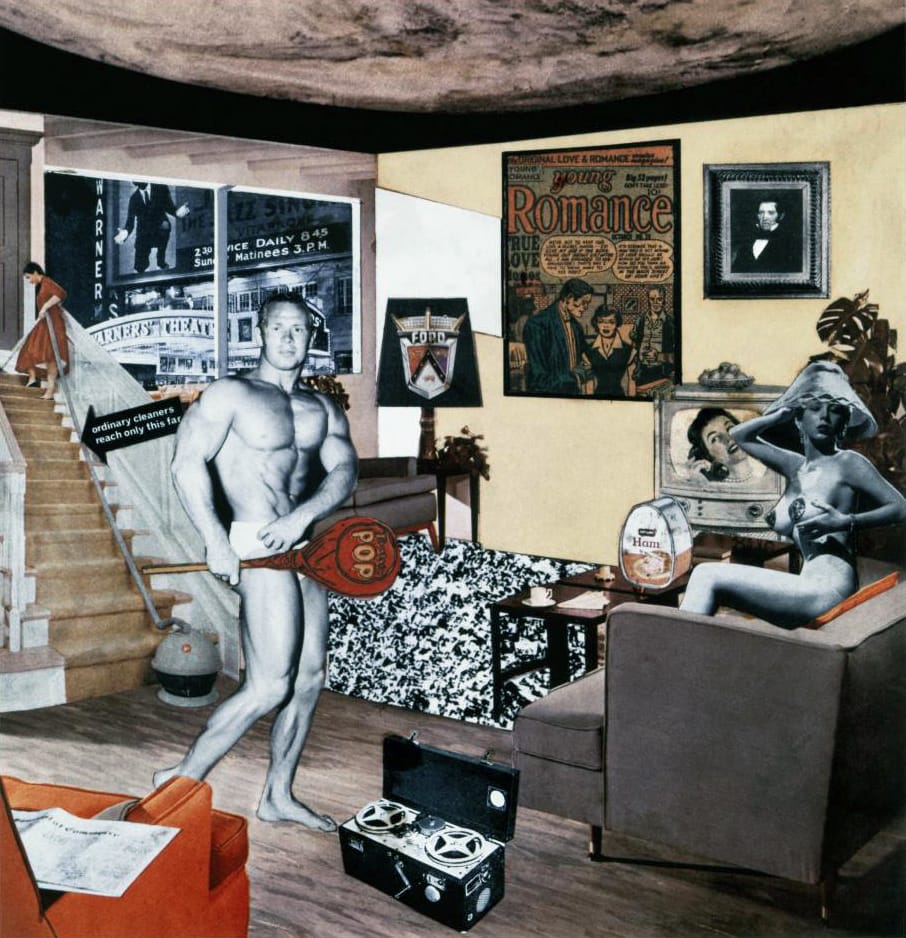

Just what is it that makes the QR code so different, so appealing?

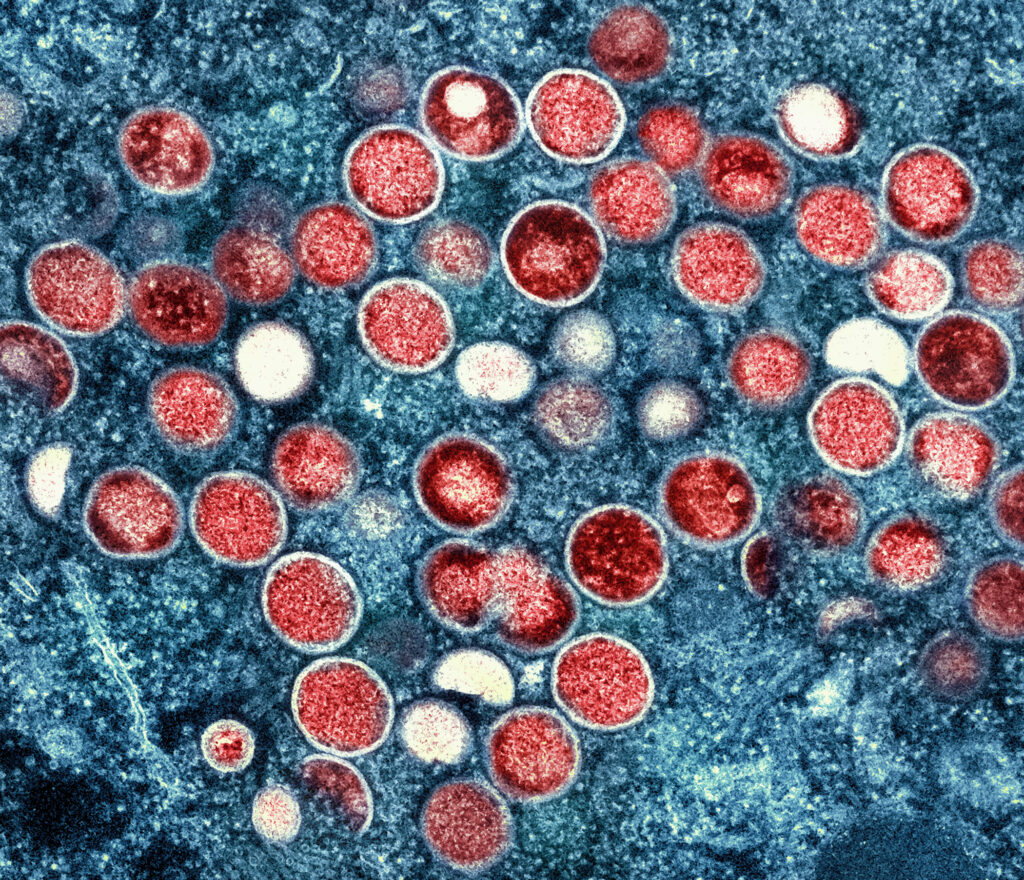

Tap your card to check in. Scan your QR code to verify your vaccination status. Use our app to report your symptoms. Receive your results by text message within 48 hours. We’ll notify your recent contacts on your behalf. These sequences became familiar to all of us in 2020. But to the many thousands of mostly gay men accessing sexual-health services in some of London’s busiest clinics, they have been routine for years. In 2022, such ‘management’ of sexual health looks like the perfect rehearsal for the generalized biopolitics which has become the norm for all. Gay men’s observance of the clinic’s commandments has undoubtedly contributed to bringing the rates of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections under control. It has also made sex feel more consequence-free than ever. But this comes at a cost: Monkeypox exposes the catastrophic trade-off between technocratic biopolitical rule and our own, compromised ability to act as moral agents. Will the affected populations do as they’re told and queue up for the pox jabs in exchange for the illusion of moral certainty as billions did during Covid?

Even though the World Health Organization is now crowd-sourcing a new name for the disease to “avoid offense”, Monkeypox once again raises the tension between control of populations and individual behaviour. Should risk-taking gay men be expected to take specific precautions or to curtail their sexual behaviour, particularly given that the Monkeypox vaccine is in short supply? Entire populations were commanded to obey extremely restrictive rules in the name of the vulnerable during Covid, yet there has been a reluctance to openly consider the same logic when it comes to gay men.

The state has proved it is not above applying draconian social and psychological pressure on subjects to conform, even where evidence for the value of such conformity is severely lacking. When the British government consulted its behaviour sciences expert unit in March 2020, its advice was to increase “the perceived level of personal threat” from Covid, advice which the body’s members later described its work as “unethical” and “totalitarian”. But because these interventions were justified as crucial to protecting the vulnerable, any kind of psychological manipulation seemed acceptable. But we are far more squeamish when it comes to the ways in which people express their desire. Why?

People have sex. They have a lot more sex than one may imagine, and they likely have even weirder sex now than Kinsey captured in his Reports in the 1940s. The recognition of this fact gave rise in the twentieth century to numerous social technologies that sought to regulate it. The high cost of unwanted pregnancy, for example, meant that avoiding sex before marriage was common sense prior to the introduction of contraception but not since. The lack of recognition of the variety of human sexuality, on the other hand, has sparked plenty of conflicts because even in the most restrained of societies, breaches of the sexual protocol are commonplace.

Unregulated sex continues to carry other costs, with the alarmingly high rates of teenage pregnancies in the UK at the turn of the century one example. It also brings about an escalation in the spread of sexually transmitted diseases, some of which, like Chlamydia, have become so commonplace that they are both easy to ignore and a threat to antibiotic resistance. Others, like HPV or even HIV, have become largely preventable for developed healthcare systems. But like every new outbreak, Monkeypox tests the efficiency of the technical preventive and treatment protocols in tension with the fading moral basis for social interventions into the private lives of others. To keep up, new social and biological technologies for mitigating emergent risks are continuously being invented.

With teen pregnancies, the state’s intervention depended mostly on moral imperatives propagated through sex education. However, when it comes to solving either the more prevalent or the now more pharmacologically-controllable problems like HIV, the state’s apparatus relies on a libertarian paternalist ‘nudge’. The nudge aims to make an individual’s interaction with the healthcare regime simple and convenient, if not ritualistic.

[ppwp passwords=”monkey bruno” whitelisted_roles=”administrator, editor” headline=”” description=”This text was published in Compact behind a paywall.” desc_below_form=”Get in touch if you’d like to read this text.” desc_above_btn=”” label=”To continue reading, you need to enter the password.” error_msg=”Please try again or get in touch if you don’t know the password.” ]A visit to Dean Street Express in London’s Soho, Europe’s busiest sexual health clinic begins with a multiple-choice dialogue on its website, where the options include “my job involves sex” and “I’ve got discharge from my penis.” Appointments are booked online, although demand usually outstrips supply. On arrival, check-in is effortless with a QR code on a membership card, and recent sexual history queries are answered on an iPad. Pop songs play in the waiting room. In funkily designed cubicles containing instruction videos with a motivational soundtrack, anuses and throats are swabbed, and urine is collected. The barcoded specimens are then collected via a pneumatic tube. Conversation with the nurse and the taking of a blood sample for analysis is effortlessly quick. PrEP (pre-exposure prophylactics, a medication taken before sex to prevent the transmission of HIV) is available in three-month batches to take away, few questions asked. Within hours, text messages arrive with an all-clear for HIV, Syphilis, Chlamydia, or Gonorrhoea, or a link to book an appointment for treatment. All of this is easy to fit in the busy homosexual’s afternoon.

The look and feel of this service wholly conceal the reality of the sexual activity that precedes it. The tasteful chandeliers that adorn the waiting rooms of the clinic’s sister location where one presents for follow-up treatment are designed to help everyone forget that the assessment questions include “Do you inject drugs during sex?” and “Is your partner threatening you sexually?” The clinic knows that people have sex, but it wants them to forget about it, at least when it nudges them towards a path of sexual health through medication, the only way it seems to know. Recently, London clinics found an even more efficient way to do this, offering a free and easy-to-use home-testing service whose checkout experience is more pleasant than Amazon’s. In the age of 23andMe, the DIY pricking of fingers for HIV tests has been all but gamified.

It is easy to forget that this healthcare relates to the actions of individuals. On the gay hook-up app Grindr, the vast majority of users claim to be on PrEP (in their profiles some still list their Covid vaccination status and a few already mention Monkeypox), a signal that in their minds, HIV has been relegated to a bureaucratic past as infection rates have been falling. But how much of this is an algorithmic illusion?

For me, the question became unavoidable during a visit during post-Covid healthcare chaos to a less high-tech sexual health clinic in East London. The mobile-friendly website became an always-busy phone line. The waiting room where I spent over two hours was offensive to the tastes of a discriminating gay man, and my patience was tested by having to speak to three healthcare professionals of escalating seniority before I could receive what I needed, despite having already described my symptoms to the receptionist in front of strangers.

This is nothing out of the ordinary in any mass healthcare system, yet the questions I was asked by the physician whom I watched straining to remember the shortcut codes for recording my sexual behaviours in a clunky database left me feeling that I was being assessed not only for how much and what kind of sex I was having, but why. A follow-up text message then asked me to confirm that I had notified all my sexual partners of the risk I had exposed them to, in language that read more like a pastor’s than a doctor’s. My feeling of discomfort came from the fact that in this lower-budget setting I was asked to act as an independent moral agent.

As with HIV, Monkeypox has spread first among men who have sex with men. But the idea that healthcare messaging and interventions should be directed at the population most affected has been denounced as homophobic. But is it really homophobic to ask whether the group currently most affected by and most likely to propagate the virus should think about its role in spreading the infection? After the closures of schools, theatres, and restaurants in the name of Covid, wouldn’t closing sex clubs be an equally reasonable response to the threat of Monkeypox?

This question is moot because such closures would likely be as ineffective as the Covid ones were and because human sexuality remains taboo even among those having the sex. It is far easier to comply with the demands of the clinic: in the UK, the limited supply of Monkeypox vaccines is being offered to men who have sex with multiple male partners. In London, appointments are in short supply, signalling that take-up is high. I have a friend who exaggerated his sexual activity to qualify as ‘high risk’ and therefore become eligible for the vaccine. Before PrEP became widely available three years ago, he would be paralyzed by the idea of ‘risky’ condomless sex. Now, his individual responsibility has been medicated away.

This inoculation impulse entirely avoids the reality that some gay men do get up to some incredibly stupid and risky things. Peter Darney’s play Five Guys Chillin’, constructed from interviews with participants in London’s chemsex scene narrates drug-fueled orgies that frequently go on for days during which addictions to drugs and sex compete to cause the greatest damage. Should we normalize such behaviours under the umbrella of diversity? We may not have a choice. I was not surprised by one of Darney’s characters describing sex with a man infected with Gonorrhoea as “better” because his cock was “self-lubricating” with the infectious pus. Darney told me that he knew many more men involved in the chemsex scene that he could have interviewed and that most were keen to share their stories when they were high. When sober, they were racked with guilt.

Is this behaviour more likely to aid the sexual transmission of diseases than monogamous coitus? Of course. Is it, in any dimension, immoral? The participants’ feelings suggest that sometimes even they think so. But if we agree that some behaviours are socially or individually undesirable because of their possible consequences, the sexual health clinic is not a space in which their ethical dimension can be discussed. Doing so would inevitably interfere with the clinic’s mission of addressing the problem at a population health level. Guilt, however, is not an efficient prophylactic because… people have sex. Technocratic nudges are no good at solving ethical problems either, yet there seems little room for any genuine discussion of practical reason when it comes to sexual behaviour.

Is there a way to bring these concerns together with the recognition that in the pursuit of our desires we willingly do things we know to be bad for us and worse for others, while understanding that the state’s below-the-board management of our morality is both ineffective and offensive to our freedoms? Covid proved too great a cognitive load as we were forced to reconsider so many of our instinctive social instincts as harmful. Perhaps the reality that the sex lives of others are even more difficult to control will help us develop the capacity to think about morals and biopolitics anew.

[/ppwp]Main image: Richard Hamilton, Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?, 1956