On 16th August 2021, the world’s media gawked at images of Taliban fighters in Kabul completing their takeover of Afghanistan. There was no customary footage of armed fighting or sound of gunfire. Instead, we saw the Taliban command in an impromptu photo-op in the former Afghan president’s office. In the city, the Taliban fighters explored an amusement park, filming themselves on a children’s merry-go-round and riding around in bumper cars. Elsewhere, the fighters pictured themselves trying out the facilities of a hotel gym. These scenes defined this bloodless coup that reversed the course of a decades-long effort by the US and allied forces to bring democratic rule to Afghanistan.

Unlike in previous watersheds, little is momentous about these images. No statues were toppled, no blood was shed, no buildings were destroyed. None of the poignancy of Lee Miller in Hitler’s bathtub either. Only the Taliban fighters’ wonder at the land they inherited with all its traces of war and conflict, but also with symbols of the civilisation that the Americans tried to instil in the region. Those symbols: fairground rides and treadmills. Disneyland.

In a series of essays published in 1991, Jean Baudrillard suggested that the Gulf War never happened.[1]Jean Baudrillard, The Gulf War Did Not Take Place, trans. by P Patton (Indiana University Press, 1995). Extending his attention to the media presentation of the war effort, including an infamous CNN interview in which US soldiers admitted to obtaining situational information from television news rather than from their military command, Baudrillard concluded that the Gulf War was an act of violence performed for the benefit of the cameras and spectators in the invading country. Whatever atrocities were committed on the ground and however many Iraqi lives were lost, the Western news networks presented a pre-scripted, edited, and decisive simulated image of the event that perfectly resembled what their audiences understood to be a war and a justifiable war.

For Baudrillard writing at the onset of the conflict, the Gulf War was the first example of a hyperreal war, a simulation that needs no reference to any reality. What the TV screens showed, as Michel Auder documented in his 1991 video work Gulf War TV War – a montage of news clips and reports marking the launch of Operation Desert Storm – was an idea of war conceived entirely between the White House press room and the TV studio, bookended by advertising breaks. Whether these images had anything to do with the reality in Iraq soon became irrelevant.

Hi8 video and mini-DV transferred to digital video, 102′. Courtesy of the artist and Martos Gallery, New York.

Thirty years on and at the end of a different war – although not in an altogether different simulation – the images of the Afghanistan conflict lack the bombastic commentary of Auder’s TV archive. US and allied forces have long stopped relying on the emotional charge of the hunt for Osama Bin Laden. Reflecting on the drift of the (in Baudriallrd’s take) placeless war from Iraq to Afghanistan, the poet and journalist Bilal Khbeiz noticed that the images that now represented the conflict were completely silent.[2]Bilal Khbeiz, ‘The Dead Afghani before the Camera and before Death’, trans. by Walid Sadek, E-Flux Journal, 57, 2014]. Unlike the documents of previous wars, photographs of dead Afghans needed commentary to acquire meanings. When did this child die, how, where, why? These answers are necessary, else the images cannot compete with the myriad other images and the simulations to which they contribute. Baudrillard’s war game finally become a fully-fledged simulacrum: not only did the representation of the Afghanistan conflict not match its reality, but there was also no reality to speak of.

The fundamental unsustainability of Baudrillard’s take lies in the fact that simulating war is the privilege of an invading force imbued with a tactical advantage, sophisticated military technology, or at the very least an imagination that can no longer distinguish reality from a sign that it is presented with. In the Gulf conflict, the US and NATO allies had access to all three. That the Iraqi people did not is well documented, but even the documents of their reality are liable to the logic of the hyperreal. For example, Monira Al Qadiri’s 2013 video Behind the Sun – an intense, flame-filled record of the burning oil fields of Iraq overlaid with archive readings of Arabic poetry – gives into the ideas of ‘petroculture’, a mode of engaging with the region’s reality through the prism of the economic interests of those who would map and simulate it. In Khbeiz’s words, the Afghan’s place before the camera now only serves to simulate his death.

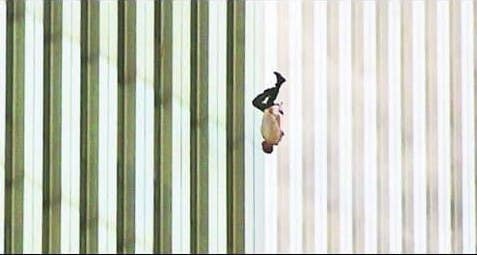

Baudrillard saw terrorism as an abnormal reaction of an overly powerful hyperstate that turns against itself. In the hyperstate, terrorism is inevitable, but as a side-effect, it could temporarily provide respite from the march towards the simulacrum. But just as he was pessimistic about the revolutionary potential of abreactions available to individuals, such as escapes into drug use, Baudrillard was conscious that terrorism was unlikely to break the simulation for good. The Al-Qaeda terrorists of 9/11 seem to have known this: the attacks on the Twin Towers (which Baudrillard described as emblems of the “divine form of simulation” already in 1976[3]Jean Baudrillard, Symbolic Exchange and Death, ed. by Natalie Aguilera, trans. by Iain Hamilton Grant, Published in Association with Theory, Culture & Society, 2nd edn (SAGE Publications, 2017).), were staged as though for the camera and played perfectly into the simulation script. After only a momentary respite, the images of 9/11 advanced the simulation rather than broke it.

What images will we be left with after this latest act in the Hyperwar on Terror? Media commentators have been fast to juxtapose the harrowing images of Afghans attempting to flee Kabul falling to their deaths after hopelessly clinging to the fuselage of US evacuation aircraft with the photographs of Americans jumping from the Twin Towers on 9/11. Perhaps this pairing would have been correct if we didn’t already know that the terrorist glitch in the unfolding simulation was only temporary. Baudrillard would instead see the 9/11 images alongside the videos of Taliban fighters at the fairground and in the gym, because only those images – documents of a version of hyperreality that the US occupation exported to Afghanistan – can remind us that there once was a reality outside, just like he argued that Disneyland reminded Americans that America was not, in fact, Disneyland itself.[4]Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, trans. by S F Glaser, Body, in Theory (University of Michigan Press, 1994), pp. 12–14.

Cover image: Lee / fickr

Notes