notes and notices are short and curt reviews of exhibitions at (mostly) London galleries.

- Karimah Ashadu

Tendered

★★☆☆☆Camden Art Centre, LondonCurated by Alessandro Rabottini, Leonardo BigazziOn until 22 March 2026Ashadu’s films are as banal as they are overwrought with glib signifiers. Take King of Boys, a five-minute survey of butchery in a meat market in the slums of Lagos. The document is trivial on the face of it: knives hack through meat in the open-air stalls, yet not even their unsanitary conditions are worthy of note. Ashadu captured this scene through a piece of translucent red plastic, as though that somehow bestowed it with significance. She is aware of the filmic tradition borne out of such images yet is unable to advance it.

Next, MUSCLE, a glossy skin flick with men working out in makeshift Nigerian gyms, links vitalism and liberation. But even its message – half Riefenstahl’s Nuba, half Denis’s Beau Travail – is convoluted by a redundant sculptural installation which glibly adds capitalism to the semantic mix. Cowboy fetishises a stable boy with a scripted confession. But even its elaborate two-screen projection, which contrasts the mare’s trot with lazily composed images of the sea shore, fails to bring this non-story to a satisfactory end. All this takes too much room (five months in the institution’s programme) but offers precious little.

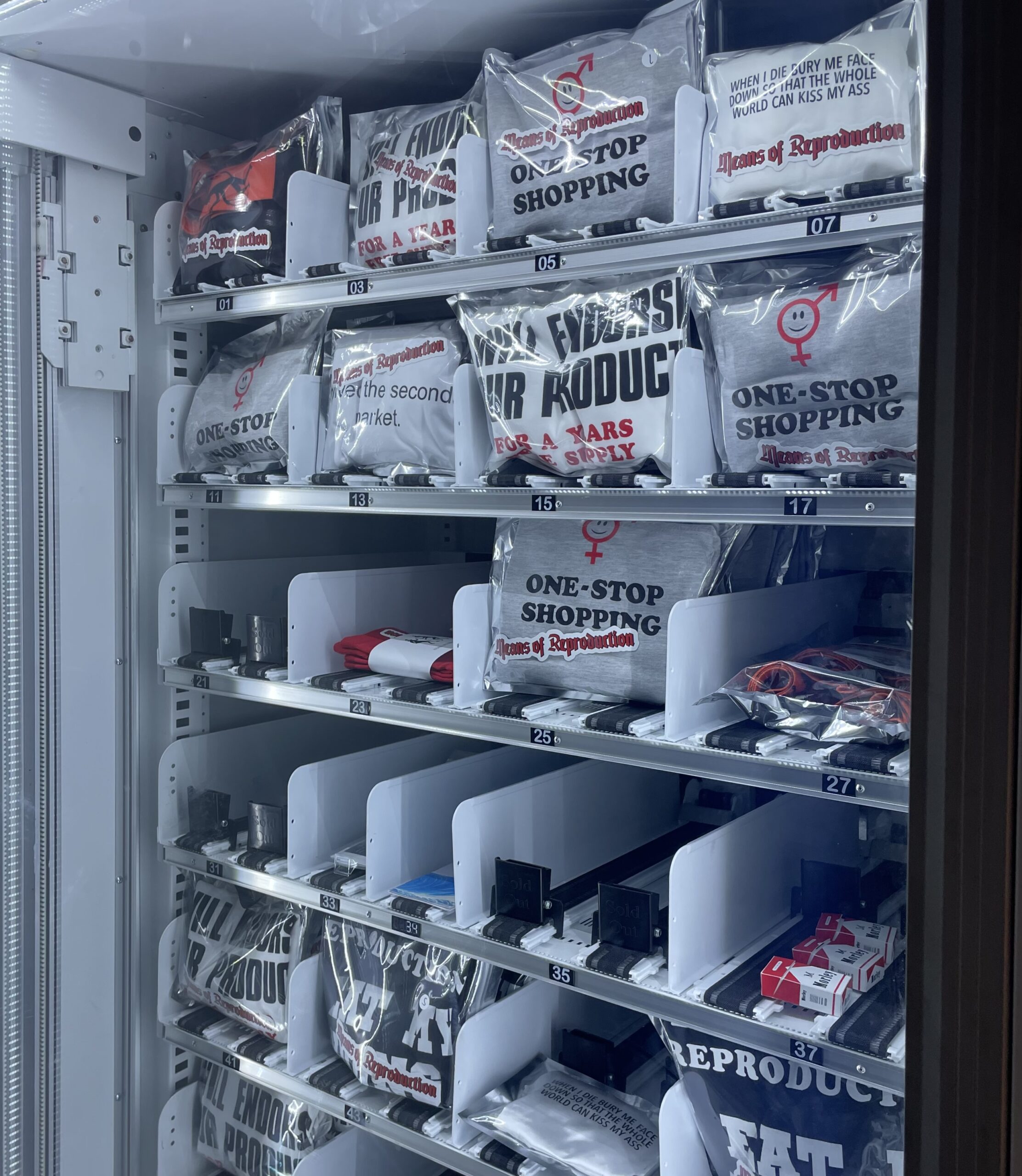

Means of Reproduction

★★☆☆☆Emalin, LondonCurated by Stanislava Kovalcikova, Jeppe UgelvigOn until 19 February 2026Turning the gallery into a gift shop – of arty t-shirts, tote bags, and homeware – is the dealer’s gimmick of last resort. It turns critique itself into a commodity, revealing, to anyone still somehow unaware of it, the art object’s elusive claim on value.

The same art pop-up, perversely, denies the artefact the aesthetic efficiencies of mass, non-curated markets. The temporary stall thus gives artists the illusion of a safe space in the global supply chain. So long as they stay off the balance sheet, they risk losing track of their wares’ aesthetic merit.

These non-trading artists did, and their works are dully indistinguishable from the stock of the fashion concept store next door. The ‘meta’ of this trade, then, might well be that consumption is the greatest form of anticapitalism. What it looks like – and what it sells – is as good as irrelevant.

Wool’s convoluted lines – in bent copper-plated steel, scrawled enamel, oil, or silkscreen – encourage the belief that, despite life’s difficulties, what starts at A will make it to B and, eventually, somehow back to A again. These trajectories resemble Brownian molecular motion, as unpredictable as they are vital. Wool’s gestural compositions intrigue with their promise of inevitability, despite, alas, lacking pictorial originality qua works of art.

To name the frustration of this oeuvre is thus to make an embarrassing admission. Wool’s 2D projections are too many and reveal that their topographic trajectory is wholly predetermined. In three dimensions, the sculptural jumbles are too solid as they pass C and D to pretend that they have been part of some great discovery. There’s no room for the eye, then, no way to follow the line.

Lijn’s kinetic sculptures are prone to typecasting, except that their type depends entirely on content. Through Lijn’s long career, her trademark rotating cones and columns have borne text, abstract marks, and light projections; those have had little in common besides their spin. The two totems now doing their rounds spin yarns of enamelled wire. Elsewhere – in Tate’s Electric Dreams, say – they could have inducted currents to stop a pacemaker. Yet paired with Lijn’s abstract canvases, they turn easy to miss for the cobbled mews gallery’s architectural columns.

Which is to speak deliberately around the paintings, extracted from a series made in the early 1990s. If Lijn’s oils lack finesse, they far surpass the sculptures’ dynamism even as they are static. Are these dreams, floral fields, or psychedelic visions? No matter; how loudly they revolt against the cyclicality of their studio siblings! How spectacularly they burn!

Black is one of those artists whose career depends more on others not making work than her making some herself. Her activism, likewise, hinges on denial. She could, therefore, be a fitting prophet of the oncoming cultural apocalypse. She has, alas, often preferred to be among its horsemen.

This meagre exhibition, comprising half a dozen lightweight text roundels, is more rant than Revelation. The paintings spell nonsense phrases – “very oxyn in dyed tulle also shall…”, “even yearners to riot…” – corrupted from the articles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Indeed, the rights regime is crumbling (even the exhibition’s title anagrammatically turns “human rights” into a joke), and Black wishes to reanimate it by painting in references to past revolutions and astral futures.

But one would guess none of it from the paint, and Black cannot have thought of her role in the collapse for more than a moment. Her blink-and-so-what aesthetic is unequal to the task; it outright embarrasses the gravity of her subject. These works’ greatest value, then, is to confirm that their intellectual primacy is truly over. What’s wrong with rights makes no right with painting.

Evacuating a two-up two-down 1970s council home seems like overkill for a weekend pop-up exhibition. A visitor who makes it past Knowlden’s steel spike sculpture – like an exhausted porcupine held together only by zip ties – that arrests would-be deniers in the property’s sunken garden, soon understands that there was no other way: the artist is an architect.

Inside, graphite and acrylic drawings, made more by erasing Knowlden’s hand than applying it, try to be subtle. This is a planner’s old trick; in art, it spared not even de Kooning. Smears, smudges, and transparencies – these images float suspended from shelf edges, sandwiched in glass panes, hung next to the kitchen island – stand out too confidently even against the house’s bright blue vinyl flooring.

The scene’s ease of means is seductive. Yet the austerity of this assembly is feigned, and it reveals that Knowlden’s is an ill-conceived war plan. Too little is at stake here: the porcupine lost its spines in vain.

The declaration, forced on visitors at the door, that this “exhibition contains distressing content” as good as guarantees that it doesn’t. Show Less purports to subvert the politics of visibility. Yet even its most ‘shocking’ component – the neon FATHERFUCKER, hung in the gallery’s window – upsets absolutely no one. Still more disappointingly for the emotion-seeker, a series of commercially produced copies of L’origine du monde, adulterated by the artists with bright spray paint, lack the frisson to add anything to Courbet’s 1866 original.

Are we so lost today that we need to paint over the man’s jest, twelve times, and call that an act of extra-special feminist reclamation? Claire Fontaine – the duo behind the FOREIGNERS EVERYWHERE neons, which inspired last year’s Venice Biennale’s title – opt for memes in lieu of substance. Their forms are easy to ‘get’ and their comforts compelling. Why, they covered the gallery’s very floor with hundreds of sheets from the Guardian, as though to elevate viewers from the plane of even that subjective reality.

But the show bestows freedom selectively: a series of declarations made in a childish hand cuts off their maker from the past and their ancestors’ sins. “I am free”, it proclaims, staking a claim on history’s ‘right side’ and #kindness. Repeat these mantras enough, and the lie becomes art.

- Theodore Ereira-Guyer, Jandyra Waters

We Lost Lots of Beautiful Things

★★★★☆Elizabeth Xi Bauer, LondonCurated by Maria do Carmo M. P. de PontesOn until 25 November 2025If mimicry is flattery, then the late Jandyra Waters’ 1980s abstractions found in Theodore Ereira-Guyer a dedicated admirer. The works share their size and palette; the painters shared a language. The two have not met, yet this four-hander tricks the viewer that Waters’ oils – in their serial form reminiscent, perhaps, of Etel Adnan – and Ereira-Guyer’s plaster and coloured glass etchings – downstream in design from Anselm Kiefer, say – were made by the same artist.

Some of Ereira-Guyer’s pigment and cement assemblies pay homage to Waters’ canvases explicitly: one glossy mess of corrosion hangs under a patchy oil pill, for example, as though in continuation of the same thought. Other pairings diverge from this pattern, only forcing the eye to draw inferences where there may be none.

Continuing consistently across the show, this game of mix-and-match throws any one-to-one mapping into doubt, only to reaffirm it. Ereira-Guyer’s tribute is, therefore, a kind of unconscious ‘abstract plagiarism’ endemic to all painting. The human mind is mimetic – all art is representation.

The phrase “vocalised gibberish”, which features in this exhibition’s introduction, is a depressing description of contemporary art’s penchant for the exotic evacuated of any aesthetics. Singh casts three toy monkeys – the see/hear/speak no evil line-up – in plaster resin, modelling them after a toy family heirloom. This somehow shows, in the curator’s words, that the artist’s heritage gives her some special relationship to this visual maxim. It doesn’t, of course, but the work’s too dull to invite the consideration of its essentialist claim.

An improvised mezzo-soprano soundtrack half-intently emanates from the sculptures, bringing, as Singh’s practice often does, more claims on cultural signifiers. Those make the fact that the room looks like a wedding cake shop at the end of a busy week more than a little incongruous. White ink prints of the plush toys on black paper, resembling the patterns a half-exhausted roller brush leaves on a bathroom wall, bring no explanation.

Where are the “esoteric rituals” and “emotional pain”? What would it take for art to look like something, anythingonce more?

How does contemporary art support the labour struggle against AI and automation? Huckfield’s question is rhetorical, surely. Her manual weaving loom, refashioned into an electronic musical instrument, adorned with Luddite hammers, offers zero insight. The verbiage in the handout – more laboured, sadly, than the artefacts – tries to intersectionalise the Industrial Revolution, proposing that Ned Ludd’s campaign against the Spinning Jenny might have been more successful had both of them come out as non-binary.

The whole thing’s a category error; art’s gender and class projections occlude matters more tightly than the cloud. Huckfield crowbars made-up heroes into past revolutions to pose as the saviour in the next one. Yet she still needed the help of eight ‘workers’ to mount her installation, not counting, that is, the machines in China which likely fabricated its substance.

Inspired in form and attitude by Manhattan Art Review.