notes and notices are short and curt reviews of exhibitions at (mostly) London galleries.

Ruppert’s quaint amalgams of the gothic, the erotic, and the extra-human are right up the hills of the uncanny valley. Leather-clad torsos sport marbled bearings. Winged monsters with penis-like tentacles drown in champagne sepia. These scenes are as enticing as they are deadly and their fan-fiction familiarity is as disturbing as their number.

This is the fodder of DeviantArt and the last year’s AI engines. But Ruppert’s charming macabres hail from the 1970s and speak of an apocalypse the artist could have only imagined. This little exhibition thus hedges retro with curio, ultimately withholding the key to this life’s dark obsessions.

Can an installation be too site-specific? Even without the help of an artist, this gallery’s quirky interior could not conceal the evidence of the site’s former life as an upscale spa. The showroom was once the steam room and the luxury marble floors tickled the feet of swimmers rather than entice would-be collectors.

Nakayama’s sculptures and paintings echo handrails, lane lines, and life rings, as if to tempt the patron’s mind to the riviera with beach sand and sailboats. These fixtures were once useful. Today, the artist’s facile interventions only expose the gimmick.

A five-armed tepee made from cheap polyester bedding – barely an iteration of the artist’s 2015 installation which turned the same gallery into a tunnel – plays host to a five-dimensional audio installation. Having captured his audience, Middleton blows raspberries into the microphone. Next door, two totems made from junk furniture, woodworking tools, and grandma’s knitting basket float suspended sideways from the walls.

Spring is time for spring cleaning. But artists are already thinking of summer picnics and lazy Sundays spent in bed or the potting shed. But the mass-produced safety blankets are too on the nose next to the mass-produced retro. An interest in material is core to this practice but Middleton mistrusts his instincts. A recklessly messy prose poem which footnotes the artist’s WhatsApp inbox speaks of “authoritarianism”, “getting lost” and “exhaustion”. It thus gets from nowhere to nowhere, as regrettably does the exhibition.

The gallery is empty except for a couple of battered wooden benches styled from the design of a violin. A single speaker periodically pipes isolated musical passages performed by the same instrument. This sound is extracted from an Elgar recording on which Leon’s grandfather, a Jewish refugee, played second violin.

The music is lost without context in the open-plan gallery dominated by the invigilators’ chatter. A series of musical ephemera from the artist’s collection half-heartedly situates the project in post-war Birmingham of the 1940s, but also too vaguely in the sprawling lineage of Beethoven, Schubert, and Vivaldi.

The gallery text finally explains the aim of this confusion: Leon believes that the symphony is “cacophonous” and wants to rescue his ancestor from the oblivion of music. He disowns the tradition in which fulfilment came from playing part in a collective, rather than individual endeavour. This could have been a tender homage, or maybe a political charge found in a life’s work. Instead, this embarrassing display indicts today’s second-fiddlers with narcissism and egomania.

Pritchard’s practice, once happily confined to the surface of a ready-made canvas, has found a new scale in this exhibition. The gallery’s basement sinks under the weight of three concrete assemblies. Their twisted shapes, textures, and menacing dimensions would make a great backdrop for a reality TV programme on Brutalist architecture and earthquakes.

Death by debris falling from building façades is an artist’s occupational hazard. A couple of collages that accompany Pritchard’s future rubble suggest that collapse was not far from the painter’s mind.

It is a matter of course that one end puts another in perspective. By unavoidable contrast, Pritchard’s smaller maquette sculptures lack either the menace or the lightness commanded by her concrete extrusions. Their number, excessive given the showroom’s subterranean lack of a skyline, leaves the exhibition unbalanced and lacking a guiding principle.

- Shu Lea Cheang

Scifi New Queer Cinema, 1994-2023

★★☆☆☆Project Native Informant, LondonOn until 20 April 2024Warning visitors that Cheang’s video works “contain explicit sexual material, nudity, and strobe effects” as they leave the premises makes this gallery the champion of understatement and misrepresentation. The Taiwanese activist Cheang may be a pioneer of ‘alternative’ and ‘queer’ cinema who warrants a PhD thesis on post-punk, post-AIDS, or an altogether post-sex future. But even a brief sample of this screening programme reveals that, above all, she is a pornographer. The gallery’s darkened screening room offers the passer-by relief through hardcore sex which he would otherwise need to search for online with keywords like ‘vintage’, ‘Asian’, and ‘fantasy’.

The gallery’s verbose text hits the queer theory tropes but does little to explain how the straight couples fucking on screen contribute to anyone’s liberation. It does even less to encourage in-depth scrutiny of the over four hours of material in the exhibition. With content this gratuitously explicit and a curator so absent, it’s a miracle that this project wasn’t shut down by the licencing, or indeed art-historical authorities.

Jones’ tableaux which capture everyday objects like tableware, cut flowers, or arrangements of light and glass are tricks of the eye that pretend to come from a past register of sepia-toned sentiments and cyanotype archive records. As objects representing objects, these works are exquisite and their tricks are revealed neither by their delicate dimensions, nor their luxury polished frames. One therefore imagines the painter’s hand applying the watercolours and oils to suedes and silks with the care once reserved for the most elaborate and delicate of photographic processes now synonymous with a nostalgia for easier truths.

But this spell must be broken. However attractive the trinkets in front of Jones’ easel and however masterly her rendition of them, these images finally inspire frustration. The lightness and slightness of the painter’s gesture cry out for a sledgehammer that would relieve the viewer of doubt and responsibility for deciding which of the scenes will stand the test of time.

Gifford’s lazy assemblages of textiles and oil paint – applied so thickly that it’s a miracle the canvases don’t bring the gallery walls down with them – are interested in little but their own form. A handful, as if to expose the artist’s obsessive yet underdeveloped idea of a masterstroke, incorporate domestic objects like the detritus of the laundry room or scraps of the bedroom curtain. Whatever stories these compositions bore in the artist’s studio, in the collector’s home they’ll only gather dust.

What good it is to be best in show when the competition is lame, crooked, or outright fake? Fischli’s Kennel Club parade of papier mâché dogs and stuffed cats is so inclusive that a plissé pug, a cross-stitch beaver, and even a tartan bunny have snuck onto the catwalk. In the gallery’s pristine interior, this motley victory parade is watched over by a canary and a feline with a fetish for denim. These natural enemies have suspended their squabbles so they can lull their prey into a sense of security as fragile as the gypsum fur ornaments that are the source of their pride.

What this contest lacks in hierarchy, it compensates for in irreverence. Fischli’s manner is not dissimilar to that of her namesake and countryman Peter (of ‘and Weiss’ fame), and her humorous affectation can today come across as insincere or imprecise. But if taken at face value, this project’s satire gets it the rosette.

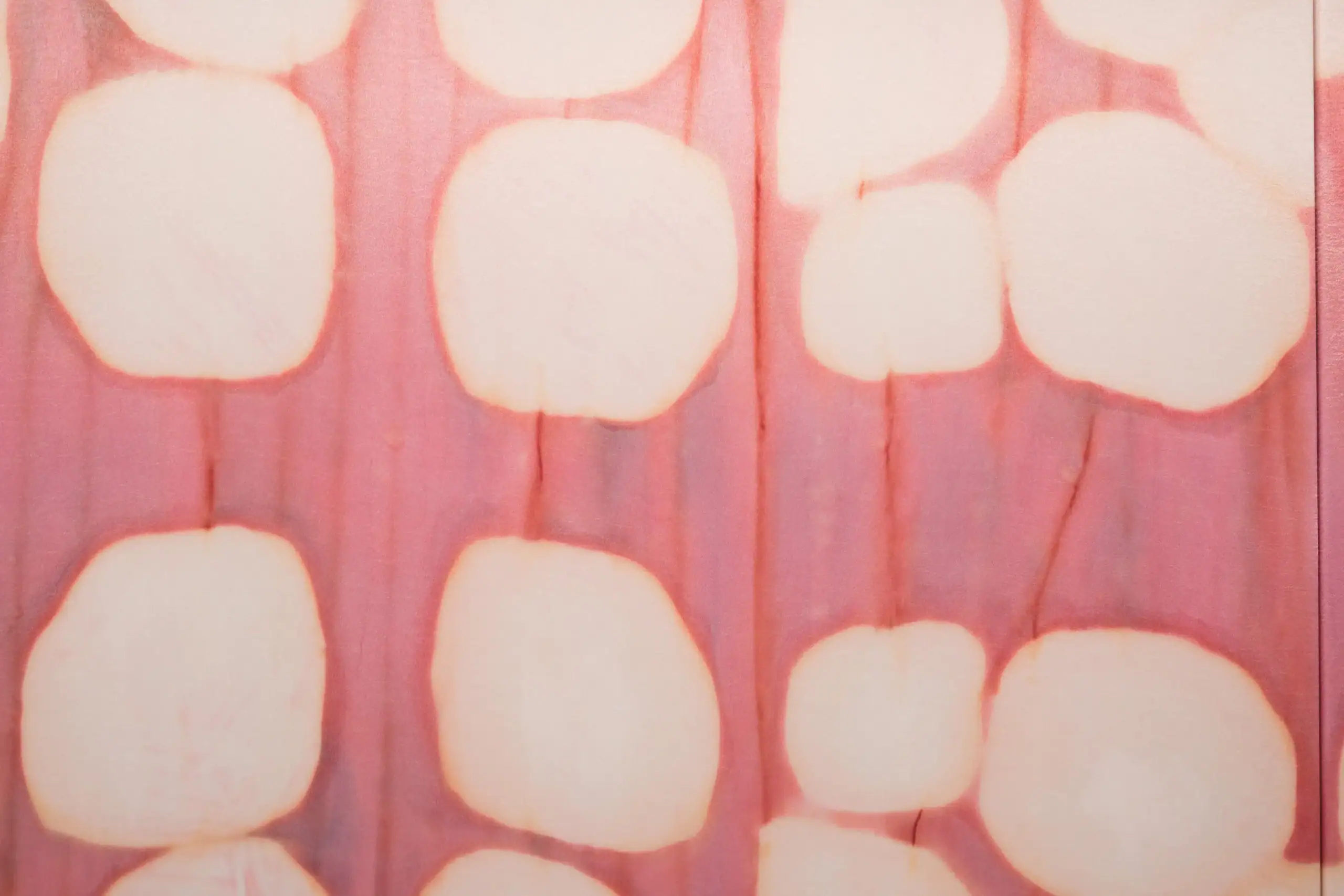

Boyla’s sky-sizes canvases rendered in bleached ink mauves, pinks, and rust are the product of meditation that turned into catatonia. These images are reminiscent of tie-dye t-shirts more than of the sun’s coronal explosions or even the blotchy floaters one occasionally sees in their field of vision. A slightly quirky hang which has the paintings hover oddly above the floor and the gallery’s lighting grid replaced by singular sources force-aestheticise this non-experience.

Rothko’s abstractions are said to have induced tears in viewers overwhelmed by abstraction. Staring at the sun here, however, barely causes blindness.

Inspired in form and attitude by Manhattan Art Review.